For the good of Europe, we need to #StopBorrell

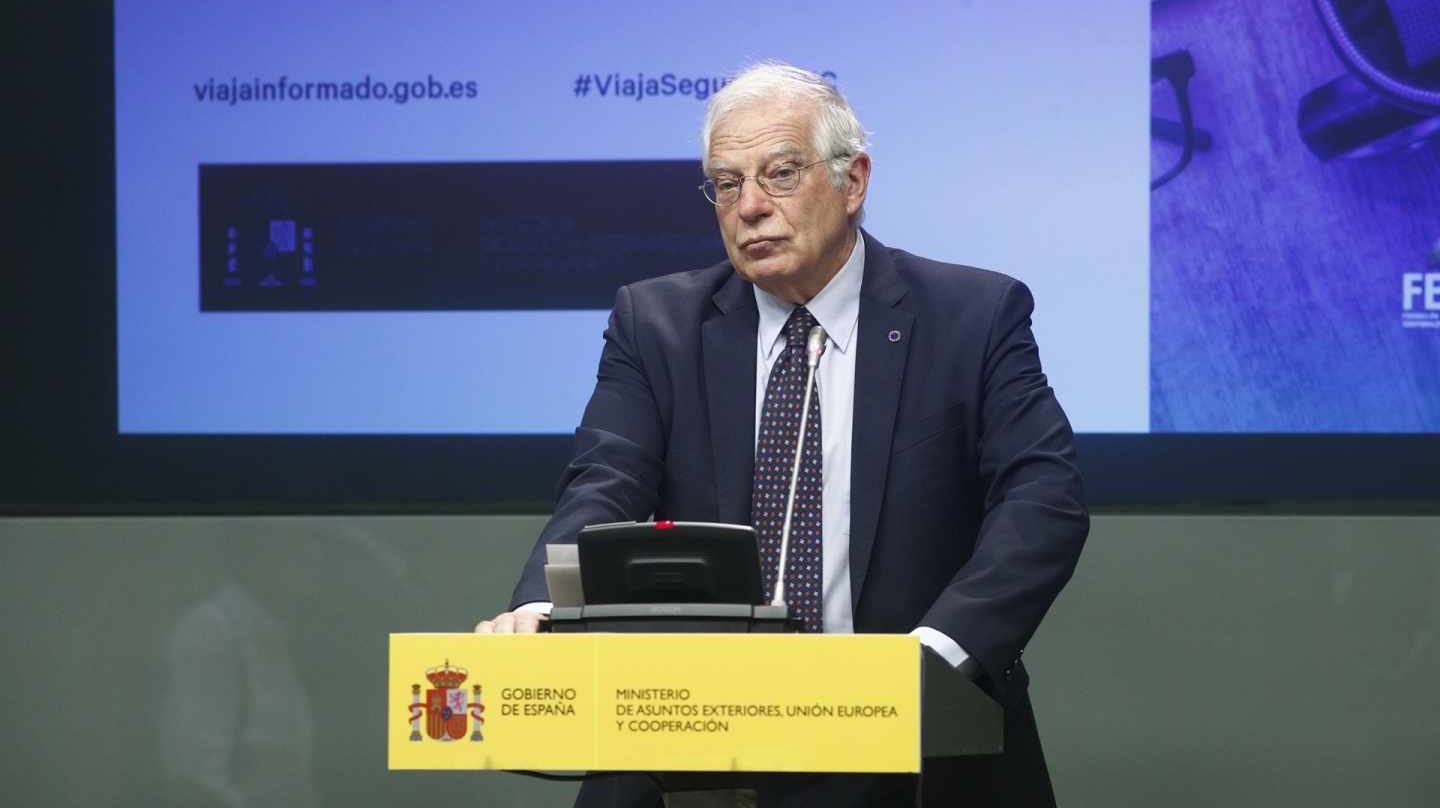

According to Wikipedia, Josep Borrell Fontelles is a Spanish or Catalan politician (depending on which language you are reading in), member of the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party and, since June 2018, Minister of Foreign Affairs, European Union and Cooperation in the Spanish Government.

With a long and colourful career behind him, Borrell looks set to add another top job to his CV, as it was announced this week that he was the European Council’s choice for the role of High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy in the 2019-2024 European Commission.

The high representative is the head of the European Union’s diplomatic corps, the 28 member states’ collective representative on the world stage. Initially created in 1999 under the Treaty of Amsterdam, with an enlarged portfolio under the Treaty of Lisbon, Borrell is set to become the fourth person to hold the post, the second from the Iberian Peninsula, following in the footsteps of Spain’s Javier Solana (1999-2009), the UK’s Catherine Ashton (2009-2014) and the incumbent Federica Mogherini of Italy (2014-).

As Charlemagne notes in The Economist, “Borrell will be the most heavyweight figure to serve as high representative”, by implication adding to the prestige of the position. And yet, paradoxically, if the European Union is serious about listening to the popular impetus for change expressed in May’s elections, if they want to be taken seriously in global diplomatic circles, and if they are serious about cleaning their image, it is imperative Josep Borrell is not appointed to the role of high representative.

It is imperative we #StopBorrell

When the appointment was first announced, I posted an off-the-cuff tweet, a one-line comment in which I broke my own golden rule of not resorting to expletives on Twitter. It was not intended to be in-depth political commentary, merely an expression of frustration with the backroom deal to impose such a divisive figure upon Europe. Yet within hours it had become one of the most widely liked, retweeted and commented upon tweets of my eleven years on the social media platform. And there’s a reason for that. Or, more correctly, several reasons.

I'm sorry, there's really no polite way to say this.

If this appointment is confirmed, Europe is fucked. https://t.co/MKnY2J4LdW

— Alan Collins Rosell 🎗 (@alancollinspdb) July 2, 2019

When Mariano Rajoy was ousted as the President of the Spanish Government in a vote of no confidence on 1 June last year, satirists across Spain suffered from a collective heart attack. Would they find another prominent Spanish politician with such a serious case of foot-in-mouth disorder as the outgoing prime minister? Fortunately, for the satirists at least, in Borrell the answer was a resounding yes.

While not exactly the European Union’s best friend, the right-wing website Guido Fawkes pulled no punches when evaluating the Council’s proposals for the EU’s top jobs. Specifically, the website claimed former President of the European Parliament Borrell “has been embroiled in more scandals than Juncker’s had boozy lunches” and even “makes Trump look diplomatic”. Ouch!

Borrell has an interesting way with words, the very essential ingredient of effective diplomacy, and an interesting view of democracy. During a press conference in Geneva, Switzerland, in March, he discarded the possibility of there being a negotiated independence referendum in Catalonia. Whilst that in itself is not a controversial remark – it is, after all, the stated policy of the Spanish Government – his defence of their position was less than diplomatic. In Switzerland, referenda are not merely a tool to settle significant constitutional questions, they are a way of life, and seeing another country refuse even a one-off referendum may seem a little odd. But Borrell was on hand to tactfully dismiss their concerns, telling the Swiss:

“We’re not a strange case, you are the weird ones. I know that speaking about referenda in Switzerland is like us talking about tortilla in Spain. It’s normal here. You vote on what time you’re going to buy bread.”

The foreign minister is a known and long-standing opponent of Catalan independence. That, on its own, is not an issue. We are all allowed an opinion, of course, and in a democracy disagreements are healthy. What is less healthy is casually insulting those we are trying to persuade of our own opinion. In a speech to party members leading up to the Catalan election in 2017, for example, he spoke of needing to heal the wounds in Catalonia following the independence referendum. “But before healing the wounds, you need to disinfect them,” he said, before disparagingly comparing the leader of pro-independence party Republican Left of Catalonia Oriol Junqueras to his local priest, saying they both “have the same physical and mental architecture.”

It is not just Catalan independence Borrell has expressed an opinion on. During a discussion on European integration at Madrid’s Complutense University in November, the very diplomatic foreign minister said that Americans were united because “they all spoke the same language” and had a “short history”, before casually dismissing the displacement and indiscriminate extermination of countless Native Americans. “They achieved independence with practically no history,” he said. “All they did was kill four Indians but apart from that it was very easy”, before conceding that the fledgling state did have to fight a brutal civil war to cement their unity.

And it is not just Catalan independence Borrell opposes. He also refuses to accept the overwhelming will of the people of Gibraltar to remain British, insisting the territory be returned to Spain, and continues his country’s refusal to recognise an independent Kosovo, despite the country being recognised by the vast majority of member states he will be representing as High Representative and the EU putting in place a plan for Kosovo to join the Union. In contrast, despite Spain’s long-held policy to oppose a future independent Scotland joining the European Union for fear of strengthening Catalonia’s own case for independence, Borrell went off script and said a socialist-led Spanish government would not veto such an application, simultaneously highlighting his own inconsistency and, ironically, strengthening Catalonia’s case for independence by fortifying Scotland’s.

As if to further prove his diplomatic credentials, earlier this year Borrell was interviewed on German network Deutsche Welle’s Conflict Zone, facing probing questions from journalist Tim Sebastian. When asked about constitutional reform, he accused Sebastian of lying and walked off the set, demanding they “stop this record”. His aides forced him to go back and finish the interview.

Not one to let the pesky journalist get the better of him, though, Borrell demanded at the end of the interview that next time he be asked questions “in a less biased way”, to which Sebastian responded, without skipping a beat, “I’m not here just to give you the questions you want, Minister”. #Burn.

It was an interview which was so iconic, it even earned a parody on the Catalan satirical sketch show Polònia, which caricatured a visibly enraged Borrell vandalising the set and intimidating the interviewer, demanding respect.

Beyond diplomacy, there is another disturbing side to Borrell’s chequered past, and that is the various financial scandals he has been embroiled in. After leaving the European Parliament in 2009, for example, he took up the post of president of the European University Institute, but was forced to resign over an undeclared conflict of interest, when it emerged he was also earning €300,000 a year as a member of the board of the sustainable energy company Abengoa.

And since becoming Spain’s foreign minister, Borrell has been fined €30,000 under insider trading rules for selling 10,000 shares in Abengoa on the basis of “privileged information on this company”. Borrell’s defence at the time was that it only represented eight per cent of his portfolio. As Guido Fawkes put it, “I’m rich, it doesn’t matter!”

Josep Borrell may very well be “the most heavyweight figure to serve as high representative”, but his appointment will be nothing short of an embarrassment for Europe. He is openly referred to as the European Union’s very own Donald Trump. His own chequered past involving alleged conflicts of interest and potential insider trading is more reflective of the much-maligned European past than the future it is striving for. And as for building bridges around the world, Borrell has shown time and again he is incapable of speaking the language of diplomacy required for such an endeavour.

Now, more than ever, Europe needs renewal, but with Borrell at the helm of its diplomatic corps, it can only go backwards. It is imperative on the European Parliament, who have the power of veto or ratification, to ensure he is not given that opportunity. Those of us who care about Europe and its future must unite and make our collective voices clear: we need to #StopBorrell!

PS: Don’t just take my word for it. Those wonderful people at ANC International, the international voice of the Catalan National Assembly, produced a highlights video of Borrell’s “greatest hits”, showing exactly why he is perfect to be the EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy.

Additional research courtesy of various members of Foreign Friends of Catalonia, to whom I am eternally grateful.